What to Expect: Proposals and Contracts When Hiring an Architect

GOAT is a New Orleans-based architectural design office that offers creative solutions in architecture, interiors, and branding for a diverse range of client and project types. This post is the second in a series where the GOAT team seeks to demystify the process of hiring and working with an architect, from finding the right firm, all the way through post-construction. We will go into detail about each step of the process based on our experiences with clients ranging from residential kitchen remodels to multi-story hotels.

After you have found an architect (or a handful) you would like to work with, you will receive a proposal for the work and, usually, a services contract to sign. These documents can be daunting at first and their contents will have a significant impact on your project’s outcomes and your pocketbook. Let’s start with the proposal:

What is an Architectural Proposal?

An architectural proposal is a document, created upon a prospective client’s request, outlining the architect's understanding of the services that your specific project will need and the cost associated with these services. While many proposals will also include additional information about the practice and their process, at its core, it is intended to memorialize the mutual understanding between client and architect as to what the project is. While it is not typically a contract (though some architects do use their proposals as contractual agreements on small projects), it is important to review the proposal carefully as, if agreed to, it will provide the outline for the contract and likely be included as an exhibit in the final agreement. Below are items you may see included in the proposal document:

Project Summary: A brief statement describing the overall project from a high level. (i.e. a 2-story addition on your home including a kitchen and primary bedroom suite). This should be the architect repeating what you have requested back to you; if this does not match your understanding of the project, something has gone wrong.

Scope of Services: A breakdown of exactly what the architect will do in each phase of the project. Typical phases include: Pre-Design Research; Schematic Design (SD); Design Development (DD), Construction Documents (CDs), and Contract/Construction Administration (CA). These services are typically the baseline and cannot be omitted from most projects. Many proposals may also include additional optional services, such as: ‘Enhanced Schematic Design’, which may include renderings or virtual walkthroughs, ‘Interior Design Services’, and ‘Construction Bidding Assistance’. These will vary widely from architect to architect, but are also critical as they may include items you assumed were part of the baseline services. If your project is large enough to require them, the proposal may also include the services of subconsultants like structural, civil, electrical and/or HVAC engineers. We will dive more deeply into each of the phases above in a future post, but below is a brief description of each baseline phase:

Pre-Design Research: This is the work done before design can start in earnest. Typically, it includes a review of your area’s zoning rules and building codes to verify you will be allowed to do your project as intended and define the parameters of the project. Often, some preliminary work is done on this front in the creation of the proposal but we like to also break it out in the proposal to illustrate how critical it is to the project. The deliverable of this phase is usually a written summary of the code research and diagrams explaining the parameters that impact the project’s design.

Schematic Design (SD): Schematic or conceptual design is the early development of the project, establishing how it will be arranged, how it will look, and how it should function. Deliverables for this phase may include preliminary floor plans and other drawings or sketches, renderings, models, etc. The Schematic Design process and deliverables can vary widely from architect to architect and it is a good idea to request examples of previously produced SD packages that the architect thinks will be similar for your project.

Design Development (DD): Design Development is a critical, but often poorly understood phase. It is effectively the transition from design imagery to a draft of the final working drawings. The DD deliverable will usually look like an in-progress, unstamped version of the final Construction Drawings. Because it often causes confusion for clients that are new to the process, some architects will combine it with the next phase. These preliminary drawings can often be used for budgetary construction pricing but are not usually complete enough to finalize a construction contract.

Construction Documents (CDs): The creation of the permit and construction documents is usually the longest and most expensive phase of a project. The documents delivered at its completion will be stamped by the architect and/or the engineers working on the project and can be submitted to your local authorities for permitting and your contractor(s) for contract pricing.

Contract/Construction Administration (CA): Contract Administration is the architect’s role during construction, which is why it will often be alternatively referred to as ‘Construction Administration’. For most practices it starts at the submission for permit and ends shortly after the substantial completion of the project. A common misconception is that it should be optional or that a client may handle it themselves; however, this is highly inadvisable as every project will have questions from the permitting officials, contractor, or owner after the completion of the drawings that require clarification. The architect is also the Owner’s representative on a construction site who will know your project inside and out. Forgoing that representation and expertise is extremely risky for the success of your project.

Pro Tip: The specifics of each phase are often approached differently from architect to architect depending on their specialties, staffing, experience. Most architects have crafted their process over time and have refined it to reinforce what they are best at. That said, the baseline phases should adhere more or less to the AIA’s definition of basic services.

Fee Structure: Architects can structure their fees in a number of ways and you should communicate your preference to the architect, if you have one. Below are the three most common approaches:

Fixed Fee / Lump Sum: A total amount based on the architect’s anticipated amount of time the project will take, the complexity or risk involved in the project, the level of expertise/experience the project will require, etc. This structure is helpful for an owner to budget for the project early on; however, it makes the scope of the project as outlined in the proposal even more critical and, if there is a disconnect, can lead to change orders later.

Percentage of Construction Cost: This method accounts for the likelihood that the specifics of a project will evolve over its development and ensures that if the project gets larger or more complicated than initially thought, the architect is fairly compensated. Many clients feel this structure sets up conflicting incentives for the architect to drive up the cost of the project and increase their own fee. However, this concern can be alleviated by carefully developing your project budget before requesting a proposal and reviewing it with the architect in detail. If both parties agree that the budget is correct, this structure can work to both architect and client’s benefit.

Hourly: This method is often requested on smaller or more technical projects where the time needed can be accurately estimated ahead of time and a fair not to exceed amount set. If a project requires a lot of ideation, creativity or problem solving, this structure can set up difficult cross-incentives. Many proposals will include an hourly rate sheet with their lump sum proposal to give the client an idea of the anticipated hours accounted for and the potential cost of changes later in the project.

Project Timeline: This should be a realistic estimate of how long each project phase will take, the deliverables at each step, and often, the estimated billing at each phase. If you have a schedule in mind, you should share it when requesting a proposal. However, make sure your expected schedule is realistic, otherwise you may inadvertently drive up the cost of the project by accelerating it unnecessarily.

Reimbursable Expenses: Often there are project costs that are in addition to the architectural fees such as document printing, travel, application fees, etc. Most proposals will include a rough estimate of this cost that is often a simple percentage of the overall fee. Review this item with care, as some architects include a markup on these costs and you should include the estimate in your overall budget.

Exclusions: As important as the initial description of the project and the detailed scope of services, what is not included in the proposal can have a tremendous impact on the project moving forward. Reviewing these carefully can prevent costly misunderstandings later.

How Do I Review an Architectural Proposal?

Once received, the proposal document itself can be daunting, especially if you have requested them from multiple architects and they all look very different. Below are some tips to break them down:

Don't Just Focus on Price: As tempting as it is to skip ahead straight to the fees, be sure to read the proposal carefully focusing first on the scope and exclusions. If there is confusion there, the fees will be inaccurate anyway. If reviewing multiple proposals, it can be helpful to create a spreadsheet that compares the scope, exclusions and fees side-by-side to help spot discrepancies that may need clearing up before you make your choice. As with all things of this nature, it’s important to also not assume the lowest fee is always the best choice. Consider how well you connected and communicated with the architect to this point, their experience, expertise, or excitement for the project.

Triple Check the Scope: To reiterate, if the project summary, scope of services, or exclusions in the proposal are misaligned with your expectations or understanding of the project, now is the time to clear it up. Also consider how the proposed schedule, fees and structure, and optional services fit into your needs; if one proposal aligns well with your expectations on this front but seems expensive, ask the other proposers to match the schedule, fee structure, and additional services you want so you can truly judge the proposals ‘apples-to-apples’.

Ask All of Your Questions: It is incredibly important to request clarification on anything you may not understand at this stage to avoid costly changes later and the headaches (and heartache) that come with those misunderstandings. It's always better to ask up front than be surprised later and an architect that makes you feel badly for asking is not one you will enjoy working with. If reviewing multiple proposals, be sure to ask the same questions of each architect in order to keep the comparisons fair.

Develop Your Budget Carefully: If the fee is significantly higher than you expected, this is usually indicative of: unrealistic expectations of the typical cost of architectural services; an unrealistic overall project budget, and the architect’s fees are an indicator of future expenses to come; a misalignment of your needs or expectations and what the architect plans to provide; a misalignment between your project and what the architect is best at; or some combination of all of the above. Prior to requesting proposals, research construction costs in your area. Apps like Handyman Calculator or sites like Build Book can be helpful, but the best information will come from a local builder that does similar work or a professional estimator for larger, more complex projects. Ask the architect for recommendations in your initial pre-proposal meeting, if you need them. When finalizing your design fee budget, be sure to include optional services you would like, costs of information it is your responsibility to provide the architect (do you have a recent property survey?), and reimbursables. If these expenses are unclear, ask the architect for more information. It is also a good idea to include about 10% contingency to account for future unknowns or changes that may or may not arise. While the final cost of design fees will be a substantial expenditure, they will ultimately be a fraction of the overall project cost and investing in a good architect is the best way to bet on the success of your project.

After all that, Do I Even Need a Contract?

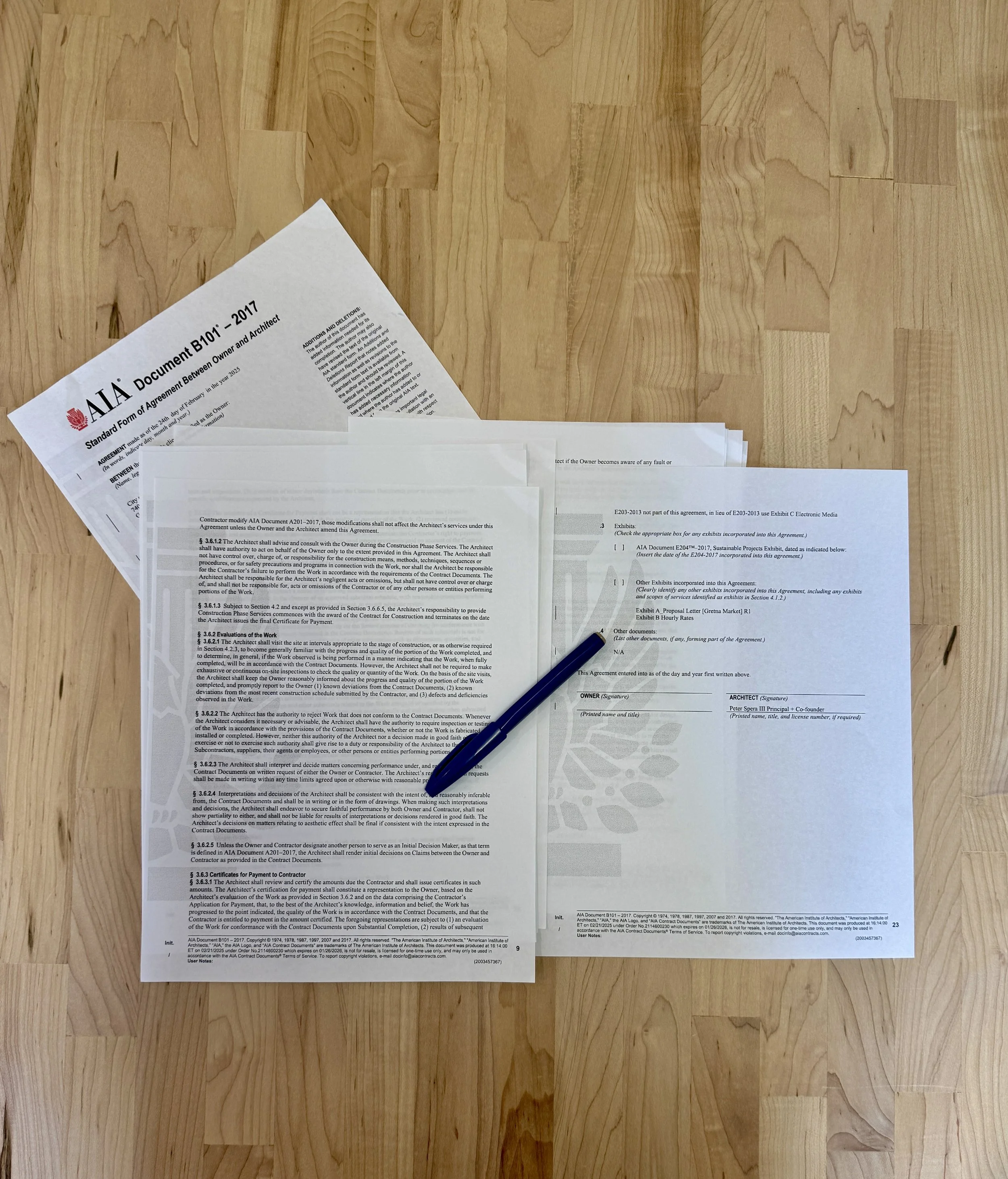

Usually, yes. The final contract, which should be developed based on the agreed to proposal, is as much to protect you and your project as it is for the architect. A standard AIA contract typically provides details on the legal obligations of the Owner and Architect respectively, describes the terms of payment, defines ownership of the intellectual property produced, and outlines insurance requirements and methods of dispute resolution. The AIA has a wealth of information to help you understand these agreements and you should absolutely take advantage of it. Their information is more detailed than anything we could provide here, but below are a few tips to help once you reach this stage:

Read it Carefully: This seems obvious, but it is crucial. It can be helpful to ask that the architect send a draft of their standard contract with their proposal so you have time to review it ahead of making your decision. While most architects use standard AIA documents, many have developed their own, proprietary agreements that likely contain nuances that are important to understand before entering a binding legal agreement.

Seek Legal Advice: We strongly recommend having an attorney specializing in construction law review the contract before signing, especially if the contract is a departure from the AIA standard. This is a significant investment, and professional legal review can be invaluable; the same professional will likely be able to review your future construction agreements, as well.

Negotiate: Even standard AIA documents can be amended or modified. If there are terms you are not comfortable with, you should discuss them with the architect. Open and honest lines of communication will continue to serve the project well throughout.

To reiterate, contracts are to protect both you and the architect in case of unforeseen circumstances and should not be seen as an indication of a lack of trust. A client and architect that are unable or unwilling to come to a mutually beneficial agreement before a project starts are unlikely to work well together once it is underway.

Next Steps

Soliciting proposals, negotiating fees, reading and re-reading dense legal language; all of this is daunting and often opaque. But once you are through it, the fun parts can start. Next time, we will dive into our pre-design and schematic design processes and illuminate how your project sausage will be made.

Look back at our previous post, How to Find the Right Architecture Firm for more insights into starting things off on the right foot.

And check back on our first post, What to Expect When Hiring an Architecture and Design Firm, to see an outline of what is coming in future posts.